The Ballad of 박은빈: The King's Affection

*spoilers abound...

The heart of most Korean drama is a love story. To those trained on Hollywood or European cinema love, Korean romance will seem light -friendship, conversation, helping, hands touching, plucking an eyelash off a cheek, and catch on a fall does some heavy lifting. Too often there's a love triangle, among lead and supporting characters, sometimes driving the narrative tension and, other times, only background noise.

A parallel story line is spiraled around this love story, like a rope that leads, as expected, to a knot. This parallel story may tackle contemporary social issues, engage fantasy or historical Joseon-period narratives. As with all shows, the writing, acting, and production value are the weak or strong fibers entwined in the making of this rope, but it is the love story that pulls us along (I know fellas, it's the sword fights).

Yet, I am surprised how often the male leads lack personality. Cool, stoic, yes, and occasionally even tearful, but rarely interesting, rarely lively. I have watched Park Eun Bin as the love interest of a ghost, twice a coworker, a pianist, a faux-cousin/supervisor, a royal tutor, and now, in Castaway Diva, a reporter or TV producer (still in ♥ ▵). Although these male lead roles trend toward stiff, personality-less characters, they do support the lead woman's ambitions and remain "by her side." As in our own culture, overcoming generations of patriarchy and gender roles is represented and, one may reasonably guess, valued by the presumed demographic for these shows.

Fortunately for 연모, aka Yeonmo (Revised Romanization) or, as on Netflix - The King's Affection, the male lead, Ji-un, was animated, smiled frequently, showed confusion, solemnity, doubt. , the romantic narrative would have suffered without

The Crown Prince Lee Hwi and Royal Tutor Jung Ji-Un approach each other. He bows.

Tutor Jung Ji-Un:" I have something I have to tell you, Your Majesty. [pause] I am going to get married."

"Why, though? If it's because of the rumors going around; don't go through with it. We knew this was going to be difficult and ‒"

"This is the choice I have made."

"I do not want to lose you, Your Majesty. And this is the only way I can make sure that happens."

"So what are you saying, then? If you don't wish to lose me, why ‒"

"This is... [pause] I think this is where I should say goodbye, Majesty.

He bows and begins to walk away.

"Stop! Don't you dare leave!"

He stops.

"I did not say... [pause] that we were finished here. You can't leave."

Clenching his fist, he begins to walk away.

"Stop, now!" Music begins to play. "I order you!"

Holding back his emotions, "Forgive me... [pause] Your Majesty"

|

| The scene ends with the Crown Prince, isolated, alone -as in the beginning. |

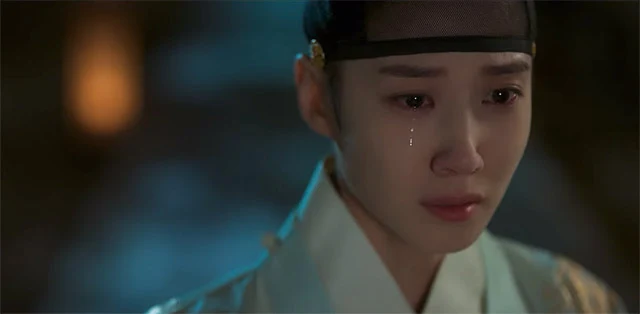

If

her use of Royal authority in a pitiful attempt to command him to stay

by her side does not tug at you -perhaps you've no heart. Of course Prince

Hwi isn't aware that Ji-un is loyal, acting only to save her life. Despite this well-worn, soap contrivance, the low-key lighting punctuated by cyan and orange, deliquescent eyes, and shallow depth of field beautifully package this culmination of twenty hours of

nearly-suspended disbelief in two characters who have walked

together and now cannot. Fate, it seems, is coming to its own conclusion.

Although the show is framed, largely, by royal palace courtyards and royal quarters, and sometimes landscapes or

villages, it never feels suffocated by them. The cinematic wide-screen format, variety of compositional devices from perspective

lines to boxing in, and closeups punctuated by catch lights and shallow depth of field provide room to breath; separating the feeling of The King's Affection from a swath of overly sharp, 4K productions. The wide screen format also offers an abundance of space to be filled with period details -stone walls, flowering trees, architecture, and

even sharply differentiated topography. Color is grounded in muted tones

punctuated by intense cyans, magentas, reds or white. The dark of night is produced with an eye for limited sight under low

light instead of artificially brightened scenes (see above photos).

This visual appeal is met by Park Eun Bin's effort to inhabit the character as wholly as she did Woo Young Woo. Few of the actor's expressive mannerisms, often visible in her other work, including Extraordinary Attorney Woo, were seen in The King's Affection. In portraying a girl surviving as a boy, she chose restraint rather than masquerade, and as the episodes progress, stoicism becomes displaced by an un-constructed, un-gendered entity. As their relationship grows more comfortable, the repartee between the Crown Prince and tutor Ji-un is smile inducing. One episode is memorable for a scene in which the petite Crown Prince Hwi physically assaults a visiting, and intolerable, eunuch. One can hardly believe that Da-mi is playing the role, self-consciously, of a young man, but is motivated by something beyond gender -a rage fired up by unjust circumstances.

|

| The tearful, desperate end. |

|

| After ingesting the poison |

Comments

Post a Comment

Go ahead and comment! I will moderate and delete the spam. Thx